Mateas Pares

Menu

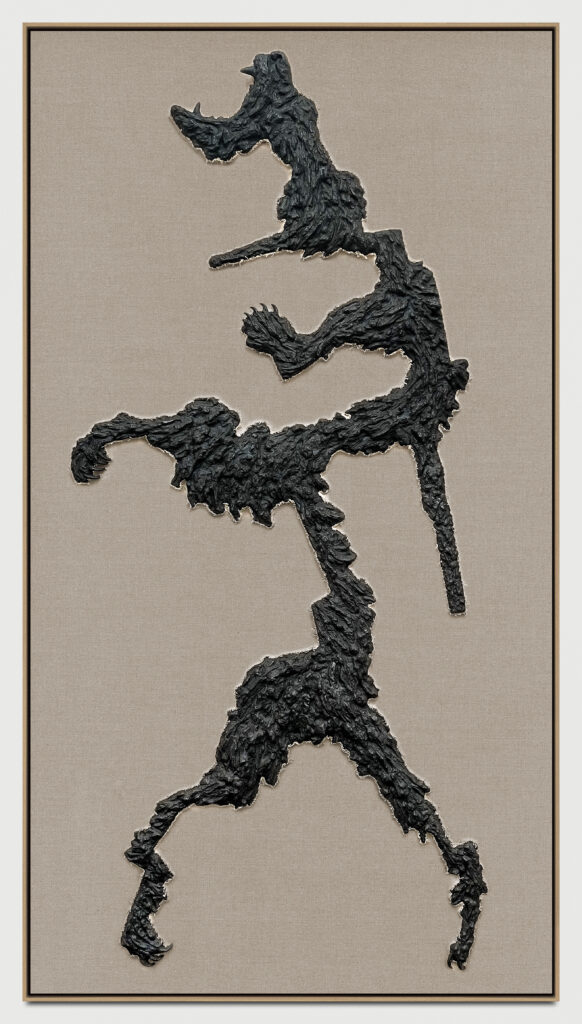

A Million Years

(2021)

A Million Years is a project based on the 2012 interactive web documentary “Bear 71” created by Leanne Allison and Jeremy Mendes, written by J.B. MacKinnon, and produced by National Film Board of Canada. Courtesy of the originators.

“Bear 71” is about a grizzly bear in Banff National Park, who was collared at the age of three and monitored her whole life via trail cameras placed throughout the valley. The project raises questions about the connection between the human and animal world, and the effects which human civilization has on wildlife. The title for “A Million Years” is taken from the original manuscript.

[...] More than a million years of evolution have prepared her to live in the wild. But let’s face it. The wild isn’t where she lives. […]

”What struck me with the text is how applicable it is on, not only the human world—animal world dichotomy, but also on the relationship between humans and the civilization. For me Bear 71 is not just a bear, but a metaphor for our struggle with fitting into the artificiality which we have created. That way it becomes deeply existential. I have been carrying the project in the back of my head for almost 10 years, and now had the opportunity to do something with it. In my practise I have created a relationship with the canvas as a sculptor, rather as a painter, by forcing different materials and objects into the canvas, and in that way charge the canvas with abstract existential concepts that can only exist in thought. By forcing Bear 71 into the canvas, and that way let it seemlingly wrestle with the canvas, I aim to raise questions about our relationship with the civilization, as biological creatures, and how that affects how we navigate in our personal and collective narratives.”

(Manuscript, shortened for exhibition purposes)

The valley is split down the middle by a freeway, and a railway.

Eighteen thousand cars a day pass by on the freeway.

Which happens to be one car every five seconds.

That’s a freight train every hour.

You have forty-four different ways to cross the highway without becoming road-kill.

Thirty-eight underpasses and six overpasses, complete with nice, “natural” landscaping.

But there’s nothing natural about a grizzly bear using an overpass.

At first we grizzlies crossed a total of once every month.

But we adapt.

Now a bear goes across almost every day.

It’s an improvement.

There’s no safe way to cross the railroad, but that wouldn’t be a problem if it weren’t for all the grain.

Grain is the number one commodity being hauled through the Rocky Mountains, and your typical grain car leaks like a sieve.

I’m not exaggerating.

Some cars are actually empty by the time they reach the end of the line.

Last year, 112,000 kilograms of grain leaked out into the park.

That’s like leaving 300,000 loaves of bread along the railway.

It was Bear 66 who taught me to stay away from the tracks.

We spent a season together, she and I, eating berries.

She had her cubs with her then.

And a mother bear is a cautious bear.

Because what’s the first rule of survival?

Don’t do what comes naturally.

If you break that rule you become a statistic.

In Banff National Park alone trains have killed seventeen grizzlies in the last ten years.

That’s one dead bear for every five kilometres of track.

People come to Banff to see what’s been lost almost everywhere else.

Everyone wants to see a grizzly bear.

But of course, no one wants to be killed by one.

There used to be this beautiful patch of bright red buffalo berries right in the campground, by the firewood pile.

Bear 66 and I used to sneak there.

You know, you’re young, and you push boundaries.

The first six months after I got the radio collar I was chased away by rangers twelve times.

They call it “aversive conditioning.”

I call it rubber bullets.

Even at a distance of a hundred feet, a rubber slug is still moving at 650 kilometres an hour.

The rangers know where I am from the day I leave my den in the spring to the day I go back to sleep in the fall.

I suppose it’s like most of the surveillance that goes on today.

It’s partly there to protect you.

And partly to protect everybody else from you.

In midsummer, people are everywhere.

This one time, I watched a young guy jog up to a certain tree and start stretching his quads.

Of all the trees in the forest, he chose that one.

It was a rubbing tree.

People think that only bears rubbed on those trees, but the cameras tell a different story.

All kinds of animals were stopping in.

Look, when you can’t pull your dog away from a tree in the forest, it’s probably a rub tree.

Here’s the thing: What looks random to you, probably isn’t.

The forest has its own language.

Maybe you can learn it with hidden cameras and test tubes.

But I doubt it.

I watched this jogger at the rub tree hang around and eat a Mars bar and update his Facebook status.

It was like he knew he had stopped there for a reason, but he couldn’t quite remember what it was.

Cubs change everything.

Up until I had cubs, I always imagined that someday, I’d leave the valley and all the lights and smells and ‘aversive conditioning’ behind, and go back and live in the mountains.

After the cubs, that just wasn’t an option.

The mountains are where the boar grizzlies live, and boar grizzlies are no joke.

They’re like Cronus in the Greek myth — they will literally eat their own young.

What I really want you to understand is this.

I was a good bear.

I didn’t knock over anyone’s garbage cans.

I didn’t break into anyone’s mobile home.

I raised three sets of cubs eating berries and hunting invisible elk in a valley that smells like hash browns.

This one beautiful day in late May, I was browsing dandelions with the cubs when two people appeared.

I reared up on my hind legs, and I was about to charge when I realized they were girls.

Just two little girls crouched down like they were praying.

So, I chased the cubs into the bush, and everyone walked away from that one.

Those girls will tell that story until the day they die.

I take a certain amount of pride in that.

They keep a video camera running on front of every train.

Why?

Liability, of course.

To keep a record in case of an accident.

It seems unnecessary to me.

If you take a hundred-car freight train moving at, say, eighty kilometres an hour, and then you slam on the brakes, it still takes a minute and twelve seconds for that train to stop.

There’s no real mystery how accidents happen.

Things that are unstoppable are a problem.

When you need them to stop.

Here’s the strangest thing I know.

200 years ago there were more passenger pigeons in the world than any kind of a bird.

Now they’re extinct.

They put the last passenger pigeon in a zoo and called her Martha.

When she died, they put her body in the Smithsonian.

Now there’s a theory that you could take Martha’s skin, extract her DNA, and build an artificial chromosome.

Then you’d insert the chromosome into the egg cell of a dove.

They estimate it will take another 200 years to figure all of this out, but in the end you’d have a living, breathing passenger pigeon again.

Just think.

The power to bring life back.

It’s hard to know what people are capable of.

They can start a revolution on a smartphone, but they can’t remember to close the lid on a bearproof garbage can.

Sometimes you do things to keep yourself amused.

This one hot summer afternoon, a ranger was keeping tabs on me at Johnson Lake.

I was observed to sniff the rope swing, and then I jumped into the water for a swim.

And I remember thinking, put that in your notebook.

Go ahead.

Analyze that.

There are times when the human world seems to disappear.

Like when an early snowstorm shakes the trees all night, and all the noises are muffled.

And the footprints go back to their houses.

And an older version of the world continues.

The last meat I ate that autumn was a deer.

He died on the new moon, and I was upwind, so only I knew he was there, because I heard the ravens—always causing such a ruckus.

I pinpointed the direction in the earth’s magnetic field, and sort of felt my way towards it.

It’s hard to explain how that works.

The deer had been clipped by a car, but made it into the woods to die.

I was lucky to get to the carcass first, but then a boar bear showed up.

So we waited.

By the next morning the boar had eaten his fill, but he didn’t leave much.

If you look backward from any single point in time, everything seems to lead up to that moment.

It was a cold, dry summer, which withered the berries, which meant we needed meat before we got into the den, but then we didn’t get the meat.

Looking back on it now, it all seems unstoppable.

The camera saw it happen.

We’d only been out of the den for one day.

It was a cold spring and there weren’t even dandelions to eat.

So what the camera saw were three brown heads sniffing for grain along the tracks.

The train took me by surprise.

I had cubs to defend, and it took me by surprise.

And I did what comes naturally.

I roared.

And then I charged.

I keep telling myself, she can make it.

But she shouldn’t be out there alone, you know.

She’s just starting her second year.

The rangers have already caught her, of course, so now she has her own radio ear tags.

She’s Bear 107.

For eleven years I did everything right.

And then I made a mistake.

Now, my cub is on her own.

More than a million years of evolution have prepared her to live in the wild.

But let’s face it.

The wild isn’t where she lives.

She’ll have to learn a new way to survive, and so will her cubs, and their cubs after that.

They’ll have to learn not to do what comes naturally,.

And I wonder.

Maybe the lesson is too hard.